Sinophiles

China: friend or foe?

Writing in the Times this weekend, Rachel Reeves signalled the Labour government’s intentions to snuggle up a little closer with their Chinese counterparts.

It follows a stretch of hawkishness in the British government towards China policy that seemed to begin when the UK government banned Huawei from its 5G networks in 2020, culminating in the country’s redesignation as a “threat” in 2022.

Labour now looks to be going the way of David Cameron and re-redesignating China a “friend”.

And it’s no wonder Rachel Reeves’ is turning her head Eastwards. The British economy is slowly tumbling down a cliff. The economy under Liz Truss was a lead balloon that came crashing, but under Rachel Reeves it’s more like a week-old helium balloon: slowly and painfully sinking and deflating. The party is over for Labour.

Inflation looks set to rise again, delaying long-awaited mortgage rate cuts even further. The cost of government borrowing is at a 27-year high, and the pound is slinking.

All the while, China’s economy continues to go gangbusters. It achieved around 4% growth last year and is projected to do the same again in 2025 (the UK is projected 1.7% growth, by comparison). It makes sense that Reeves wants a piece of the action.

A bad friend

But a relationship with China is not so straightforward. The country is in pursuit of growth at all costs: and not concerned with making friends. As early as the 90s, China was stealing secrets from the rest of the world to develop its own nuclear weapons programme, a practice that continues to this day at an astronomical scale with the multi-billion dollar theft of US intellectual property across the public and private sector. It also seems likely that they have planted spies deep in our political system - who are occasionally exposed.

It’s hard to imagine that this is a country we could ever trust - particularly if they got involved in critical national infrastructure like energy or telecoms.

Not only that, but there is a deep misalignment in values between China and the UK. In 2020, the CCP breached the long-standing “one country, two systems” arrangement with Hong Kong and began arresting academics, journalists and protestors.

Over a million Uyghurs - an ethnic group from Northeast China - are being held in concentration camps by the CCP.

And China unilaterally claimed the entirety of the South China Sea - to international condemnation - and began building artificial islands and harassing ships that have long used the route for global shipping.

This is not the behaviour of an ally.

As all of the relationship advice goes, “you’ll never change him”. If the Labour government hopes to shift Xi Jinping into a more liberal, tolerant and peaceful world leader - they will be in for a nasty shock.

A military threat

China, moreso than Russia, is the greatest threat to the Western world order. Russia’s continued humiliation in Ukraine is proof that, while geographically massive, they do not command the same militaristic might as they did at the height of the Cold War.

The Chinese Communist Party, meanwhile, has the world’s largest navy, and is massively increasing its military spending and nuclear arsenal under Xi Jinping. They have highly sophisticated weapons pointed at Western targets. The next global war will not involve tanks and rifles: it’ll involve cyberattacks, disinformation campaigns and autonomous weapons: all capabilities that we know that China has in abundance.

Befriending the Chinese government, then, might look to future historians a bit like Neville Chamberlain’s futile attempts to negotiate peace before World War 2. By giving the CCP unfettered access to our economy, we might be inviting the wolves in for dinner and expecting them not to eat us.

The alternative argument, of course, goes that you can’t change a nation by simply condemning from the outside: and that building a constructive relationship and entering an open dialogue might bring about peace and change in China. It is hard to find examples of where the Western world has done that successfully in the past, though.

The trigger to trouble will be Taiwan. The CCP are circling Taiwan like sharks, insisting that “reunification” is inevitable and flexing their military might to achieve it. Taiwan is braced for China to invade this year: and the Western world will need to decide what level of support it will give the territory against the CCP army if that day comes. Any invasion is likely to be much quicker than Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Its distance from Europe will also make support logistically more challenging, and public support weaker.

Taiwan produces 90% of the world’s semiconductors and so if China did succeed in its objective for reunification, a crucial part of the future global economy would be in CCP hands. The development of AI, supercomputers and - importantly - advanced weaponry all relies on semiconductors. If China can control their distribution, they can strongarm the globe even more powerfully than they already can.

A new world order

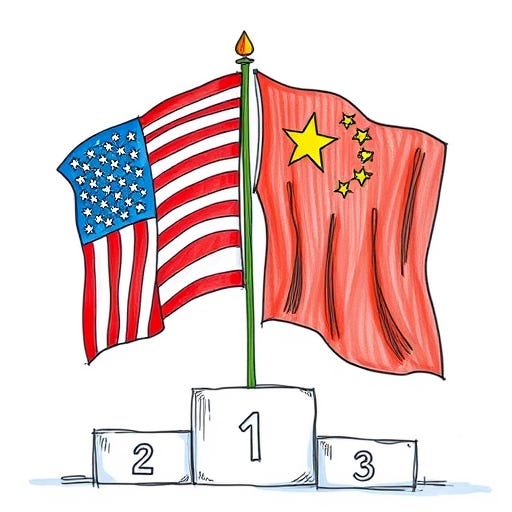

Michael Scott once said, “My whole life I believed that America was number one, that was the saying.”

Those of us alive today have only known a world where America is the dominant power. But for most of civilisation, that has not been the case. America’s dominance has extended for decades, whereas China’s extended for centuries.

For readers in China, then, the working assumption is that one day China will resume its natural position as the global leader: relegating America to a number two position.

The West should feel a vested interest in ensuring that does not happen. China is a dictatorship, with a terrible human rights record and an itching for a war. The British government would do well to remember that before they cuddle up into bed for the sake of economic growth.

the only to stop china is to stop buying they goods and mean it not like with Russia with petrol we don't buy form Russia but buy it form India who buy if form Russia