How to change someone's mind

The inner workings of Public Relations

Public Relations (PR) is a bit of an enigma. Variously termed communications, media relations, spin, reputation management, and occasionally a ‘BS job’. My favourite is “flacks”, a parallel to the common nickname for journalists, “hacks”, reflecting spin doctors’ role as taking the flack.

But what actually is this mysterious job, what do they do and how do they do it?

The foundation of the entire PR industry is essentially three, sequential objectives:

Obtain attention →

Manipulate opinion →

Influence behaviour

Winning eyeballs, hearts and minds.

For a business, it might mean getting positive press stories about the benefit of their product. For a politician, it might mean reaching voters with their life story. For a lobby group, it could be about reaching government ministers with the key points about regulation.

But how?

I’m dedicating the next two Monday Memos to a deep-dive into the inner workings of PR:

This week: How to change someone’s mind

Next week: How the news works and how to shape it

There are two differentiators between marketing and PR. One is that marketing gets a ton of money, and PR gets almost none. The second is in their objectives. Marketing is focused on separating a potential buyer from their money as efficiently as possible.

PR has a more nebulous objective: make people like the company, the product and its people, and agree with the underlying objective.

The toolkit of PR is expansive. The news is the most notorious but it can include social media, keynote talks, even billboards and ads.

Using a combination of those tools and more, here’s how the PR person changes your mind.

The short version:

Know your audience: understand them, their fears, their motivations and how they get their information

Take them on a sequenced journey that offers facts that appeal to logic and stories that appeal to emotion

Stick to your message and repeat it again and again and again

Create a hero and an enemy: people buy from (and trust) people, not logos so elevate the human components of your campaign. Align yourself against an enemy, that might be ‘the system’, a pain they experience, or an old way of doing things.

Know your audience - all of them

A PR person might want to influence prospective customers. But, unlike marketers, there are many more people they will be looking to reach.

Policymakers are often an equally or more important audience, who may be influenced to support or oppose specific regulation or legislation. Investors and shareholders might be convinced that company valuation is about to skyrocket thanks to the masterful strategy of the genius CEO. A PR campaign can sometimes have a single person as its audience: the government minister with a specifically tight brief, or the CEO of a membership organisation where a bunch of prospective customers hang out.

The first step to influencing is to know who you are influencing: what matters to them, where they get their information, what value you can add to them (and what you need from them in return).

If you’re a pesticide company, it’s too broad to simply tell the world you’re great. But you can tell the Minister responsible for agriculture that pesticides are the most environmentally friendly way to secure national food supply, by planting an expert essay in the magazine he was recently photographed reading.

Who is the biggest liability for a PR practitioner? It’s an employee. One who misunderstands the company strategy and emails 500 customers telling them you’re about to cut costs. Or one who is pissed off at some unfairness and gets loose-lipped with some journalists. So internal communications is a key component of PR: the internal stakeholder needs to be influenced and taken on a journey as much as the external one.

(Who is the second biggest liability? It is the spouse of an employee, who usually knows everything and has less impetus to keep it secret).

The elephant and the rider

Psychologist Jonathan Haidt developed a useful analogy for how we approach change. Imagine an elephant and a rider heading, full speed ahead, for your village. You want to avoid your hut getting trampled; so you need to change their route.

You need to influence three things (say psychologists Chip and Dan Heath). The first is the logical rider. The rider will use his best judgement to steer the elephant in the right direction. The second is the emotional elephant, that will follow its instincts to decide where to go. The third is the path, the environment, which can be shaped to guide both in the right direction.

To change someone’s mind and behaviour is to influence all three. Put forward a rational case, an emotional story and manipulate the environment to make the desired behaviour easy.

Here’s an example: let’s imagine you want an MP to advocate in Parliament that the government should increase funding to local youth clubs. You would:

Influence the rider by giving her statistics on how many young people depend on youth clubs

Influence the elephant with a touching story of a young person that avoided a life of crime and gangs via their local club

Shape the path by giving the MP a printed talking sheet of key stats, suggested upcoming debates she might want to speak during, and a promise to Retweet her clips.

Nobody changes their mind on the basis of the facts alone, they do on the basis of their feelings.

True influence only comes when you achieve all three, and that requires guiding your audience on a journey.

Craft a journey

If you’re a social media giant trying to convince the world that you’re a good company, you can’t do it all in one day. You need to build a journey that takes someone from a skeptic, to a believer, to an advocate.

A well orchestrated journey knows when to be loud and when to be quiet.

I had to craft a journey recently to scrap a popular product used by 10,000+ consumers. You don’t rip the band aid off in one go and tell them it’s gone. That leads to complaints, squandered trust, mean tweets.

Instead, you shift your messaging away from the product, so your CEO isn’t harping on about its benefits two days before it’s scrapped. You put him on podcasts to talk about everything except the dying product. You make it harder to access and find the product by burying it on Google and hiding pages on your website.

You create a great story about why you’re scrapping it, and road test that messaging with small groups: first employees, then investors, then key customers. And finally, you kill it: and nobody’s caught off guard, and it feels like the natural choice.

You succeed when you take everyone on this well crafted journey that ends with them advocating for you.

The best politicians do this: they tell a grand story about their government: framed around a few core missions and priorities, driven by a handful of key moments that catch the attention and shape a narrative.

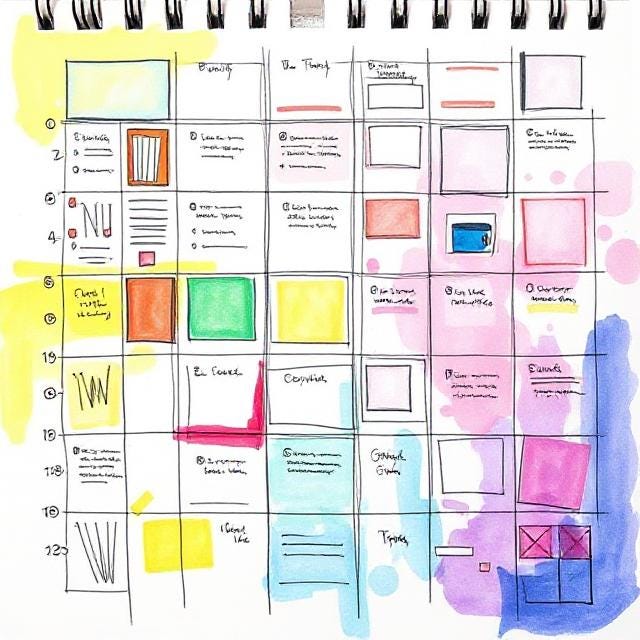

PR people often talk about the ‘grid’, which refers to the calendar of planned media moments: a timeline of the story that an organisation or campaign will take its audiences on.

Message discipline

Comms people are control freaks because they have to be. If you are trying to change someone’s mind, you can’t be seen to be changing yours.

Staying on message is absolutely vital. If you’re a vape company telling the government and parents that you don’t sell to kids, you can’t have a colourful ad with cartoon animals appearing at a bus shelter on their commute home. If you’re a political party telling voters that you won’t raise taxes, you can’t have your Shadow Minister telling Good Morning Britain that you might. And if you’re a software company telling the world that you have secure technology, you don’t want a recruiter telling potential employees that they’ll be working on boosting the terrible security.

Everyone needs to be singing from the same hymn sheet. A very common example you’ll see is a company’s CEO will claim they have 5 million happy customers, but their website says 2.5 million, and their Google Ads say over 4 million. That disconnect breaks trust.

Message discipline is about repeating the same messages, and repeating them over and over again.

Dominic Cummings and Vote Leave won the Brexit referendum because of their ruthless message discipline. ‘It doesn’t matter the question,’ was the mantra, ‘the answer is Turkey, or £350 million to our NHS’. He used the same strategy in the 2019 election with ‘Get Brexit Done’. Everyone is saying the same thing, over and over again.

And key to this is to remember that everyone cares 75% less than you think they do. Just because a campaign, or cause, or company is your whole life - the public will have just a fleeting moment with it. If you feel sick to death of saying the same thing over and over again, you are just starting to say it enough.

Heroes and enemies

You can influence the elephant with emotion, and emotion almost always requires humanity. Almost everything depends on the people factor.

For a PR person, that might mean making a company executive charming and likeable when they appear on a Bloomberg TV interview (or it might be persuading them to let their far more charming and likeable Chief Operating Officer take the interview). It could mean having a customer whose life was changed by the organisation front and centre in campaigning. Weight loss drug manufacturers, for example, would rather you hear from skinny, happy women than their very wealthy, very old pharma bosses.

In politics, this is even more pervasive. A party leader may have the best manifesto ever written, but nobody will vote for them if they are unlikeable, disconnected or even just a weirdo. Many politicians have failed this basic test: Ed Miliband the most notable. In the run up to the election, Keir Starmer worked with a vocal coach to try and have his speeches sound a bit more natural and inspiring.

As well as elevating a likeable, relatable hero - campaigns can also create an enemy. This is another emotional, rhetorical device. After all, the enemy of my enemy is my friend: a shared enemy bonds people together and creates camaraderie.

This is why so many elections see politicians play their opponents, not the ball: Boris Johnson knew you might not like him, but you both really hate Jeremy Corbyn.

An enemy doesn’t have to be a person, though. It can also be an idea, pain or concept. The traditional education system, paperwork, the incumbent.

Apple’s most famous advertising campaign pits them against Microsoft, Uber’s success depends on our frustration with overcharging, hard to find taxis. Right-wing populist campaigns have more success and emotional response because they are more comfortable creating an enemy: like ‘the small boats’.

Winning hearts and minds

There is so much more to persuasion than just this list: I haven’t even started on the tactical strategies you can deploy (like rhetorical questions, or emotional stories with a hidden message).

The ultimate sign of success is when people are doing your job for you: when Tory voters are quoting the Tory manifesto to their families, when your social media followers are posting your key talking points as if it’s their original ideas. When even your critics are chiming in on a debate you’ve created and framed.

The point is that by knowing someone, guiding their logic and emotion on a journey and sticking to the message - you can usually persuade them of an argument and turn them to an advocate. And this is a toolkit that can be wielded for good and for evil: but almost always for reasons of selfishness, to advance someone else’s business or career.

This was about the psychology and strategy of PR, next week is about the machinery and tactics. I’ll write about the news: how it works, how you get in it and why it matters.