A workerless future

We're heading to a world without work - what will we do?

In the earlier 20th century, a combination of industrialisation and unionisation brought about the five-day work week.

Since the 70s and the advent of the computer, the number of workers in ‘professional and managerial’ types of job (ie office based) - has shot up, while the number of people employed in more labour-intensive work has fallen.

And since 2020, working from home has skyrocketed - triggered by COVID but made possible by high-speed internet.

In other words, factories made the work week shorter. Computers brought workers into offices. And the internet moved workers to their homes.

There’s a clear trend: over the last hundred years, work has gotten easier and better for a lot of people. From farms, to factories, to office cubicles, and now from home.

It’s only natural, then, that the trend will continue. I suspect we are heading, in the next hundred years, to a workerless future.

There are two causes for this: the supply chain is fundamentally reinventing itself, and technology is getting more capable of doing most jobs autonomously.

The supply chain is getting shorter

If the last 5 decades have been defined by globalisation, the next 5 will be defined by localisation. We used to eat fruit and veg grown nearby, milk made in the local farm, and buy metal and fabric made by local people. Then, we got really good at moving goods from anywhere in the world to our doorstep.

But that system has proven to be terrible for the environment, at the mercy of geopolitics, and dependent on cheap labour.

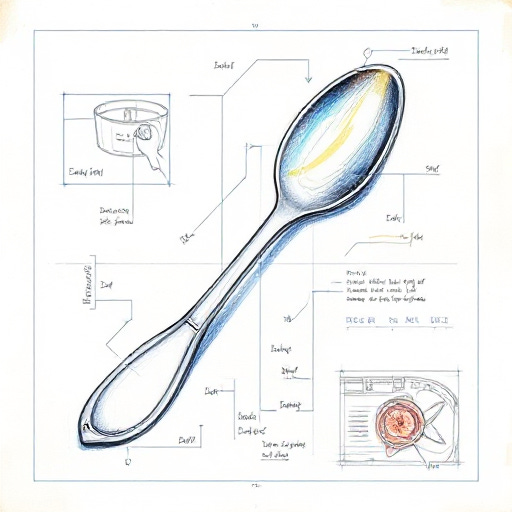

Today, a spoon is most likely manufactured in China and shipped to you. In the future, that spoon can be designed anywhere in the world and 3D printed either at your home, or somewhere local to you. The impact of this will be pretty astronomical: far fewer emissions from transporting goods, much faster delivery, and swapping low-paid labouring jobs for higher-paid designing jobs.

It takes many people to ship a spoon today. You need someone to design it, manufacturers to make it, probably hundreds of people employed in the logistics of moving it from the factory to your door. But in the future, it could take just one: a designer who creates the 3D model of a spoon, that anyone can print on their personal or local 3D printer.

This won’t happen all at once, but it will happen. Since email became widespread in the 90s, the number of letters being sent is falling dramatically. From 20 billion a year in 2004, to 7 billion a year now. That’s still a lot of letters, but it’s a steep fall - and the fall is getting steeper, with the number of letters reducing by 10% year on year. Sending and receiving parcels is at an all-time high. If 3D printing does become mainstream, that will do to parcels what email is doing to letters.

It isn’t just 3D printing that will upend the supply chain. We’ve already seen the impact of streaming: DVDs and CDs are going extinct, replaced by Spotify and Netflix. It will soon be the same for video games and games consoles - a physical good replaced by online streaming. No doubt there are other physical goods that will soon be replaced by streaming and other technologies.

And it isn’t even physical goods. Energy has traditionally been generated in huge power stations and distributed across the country. The future could be more, smaller power generators that provide energy for a local area, or even an individual property. Small modular reactors are powering the resurgence of nuclear energy: they are safer, faster and cheaper to build, and require a simpler supply chain to get power from its source to its end-point.

The overarching trend: tech-enabled localisation.

AI is getting smarter

2025 will be the year of Agentic AI.

Agentic AI takes current AI models a step further, and enables these tools to take autonomous actions.

Today, ChatGPT can help you do your job by responding to prompts and generating text. In the future, it will be able to do your job: you will give the AI an overarching objective and strategy for achieving it, and the AI will set out to achieve it independently.

This will be the biggest shake-up to the working world since the advent of the computer and the internet. The industrial age created the job of ‘manager’ to supervise the workers on the factory floor. The AI age will create a new kind of supervisor job that monitors a whole team of AI agents, completing tasks together.

But this will have a pretty profound impact on the nature of work, too. AI agents will soon be able to do many roles: initially junior ones (like assistants or entry-level positions), but eventually even senior and executive roles.

The next 5 years will also see a rapid acceleration in robotics.

Robots have gotten much, much better over the last two decades but they’ve been held back by the high amount of human intervention they require.

A robot can essentially do one task, over and over again, but if it needs to do something else or multiple things - it needs a human with a remote control or a human that can constantly reprogramme it. It doesn’t make sense for a business to fork out the high cost of a robot plus an expensive worker to programme or control the robot, when they could just hire a worker to do the job in the first place.

With AI, that’s changing. Robots are now far better at acting autonomously. Today, they can find their way around a factory floor, take readings and measurements, and make some limited decisions. Soon, they’ll be able to act autonomously - not only taking readings and measurements, but acting on the data. Prioritising their own tasks, and even doing tasks they haven’t been directly programmed for (within set parameters).

So what will we do?

It’s not obvious what technologies will replace the work we do today, but it’s clear that’s the way things are headed.

Jobs that once seemed safe from automation are no longer safe. Salesforce has paused all hiring on software engineers, citing AI’s ability to write code.

Whether it is 3D printing, streaming, AI, robotics or something else that takes on jobs, the trend is towards less and easier work required from humans.

So where does that leave us? What would we do in a world without work? Would we invent new, meaningless jobs just so we feel a sense of purpose? Some suggest we’ve already done that. Would we all live a life of leisure, funded by some form of Universal Basic Income? That’s what Democratic Primary contender Andrew Yang called for. Our entire society is built on work: so it’s hard to imagine a future without it.

There is one form of work, though, that will almost certainly rise as others fall: caring work. Jobs in childcare, mental health, social care and so on are the most resilient to automation. A sophisticated AI might be able to diagnose a complex cancer, determine the best treatment plan based on data from millions of patients that share characteristics, use advanced robotics to perform the surgery - but it will almost certainly never be able to provide comfort, reassurance and empathy like a human doctor or nurse would. A robot won’t be able to calm down a child going ballistic, or someone going through depression that wants to feel heard.

If AI augments these jobs, it will be to reduce the non-human work (admin, paperwork, data entry), to free up workers for the more human stuff.

Many economies have already undergone a pretty huge shift from goods-based to services-based. It’s not beyond the realm of imagination that the rise of AI will trigger a third shift to a caring economy: but for that to happen, there must be a serious effort to make these jobs better: less stress, higher pay.

Whatever happens, it will require some deliberate thought. A change is coming, AI could prove to be an extinction-level event for our jobs. Whether it’s creating more robot-proof caring jobs, implementing some form of UBI, or shifting to a shorter work week: now is the time for governments and employers to act.