5 predictions for the future of EdTech

The state of Education Technology

This week marks the end of what has been my six-year stint working in EdTech.

It’s always seemed clear to me that learning is a silver bullet for both individuals and for our society. For learners, a good education offers economic opportunity and a more fulfilled life. For societies, a better educated population is good for GDP and for social cohesion.

It’s a sector well worth working in, but also one that’s ripe for disruption: classrooms and lecture theatres haven’t changed all that much since the Victorian era, and most attempts at bringing in technology are clunky and doomed to fail. There’s a big prize, ripe for the taking.

Here’s what I think the future holds for the sector.

1. EdTech investment has peaked

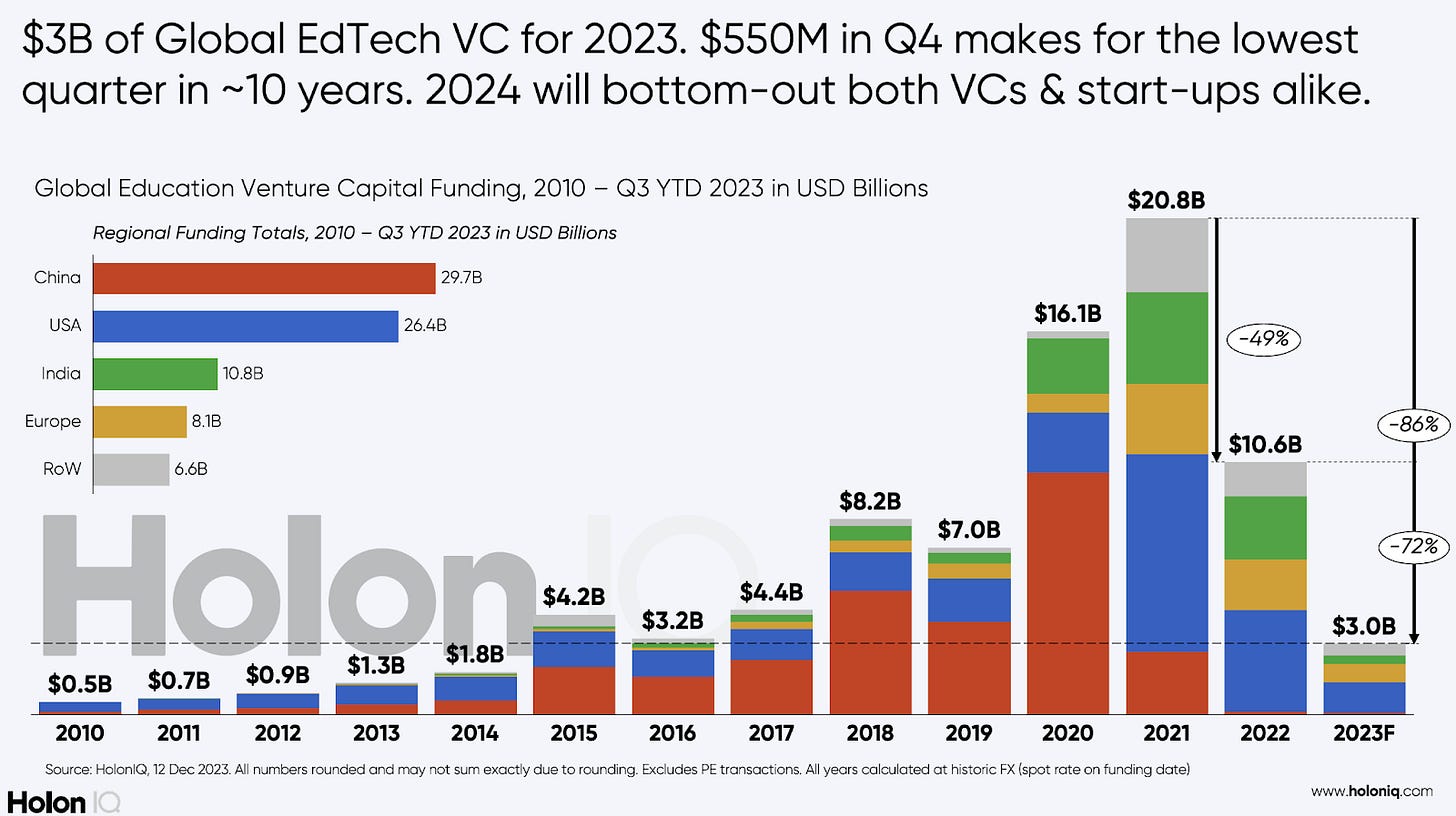

2021 was a great year for EdTech investment. Just some of the highlights:

GoStudent became Europe’s first EdTech unicorn

Indian start-up Byju’s increased its valuation to an unbelievable $18bn (making it more valuable than Reddit, Discord and WeWork)

Globally, 6 more EdTechs became unicorns

Multiverse raised the UK’s highest EdTech raise in February - then broke its own record in September

Global investment into EdTechs reached an extraordinary $20bn, after what had been an already record-breaking 2020. It was easy to believe the future was in EdTech: but the bubble burst.

Since that bumper 2021, investment into EdTech companies has plummeted and I strongly expect we are now past the peak.

What caused the boom? COVID was a huge accelerant for education technology investment, as all facets of education moved online and techno-optimists posited it'd stay that way. There was also a huge spike in adult learners with a population bored in furlough. EdTech was also a beneficiary of macroeconomic factors that saw more venture capital fluttered across the entire tech ecosystem at enormous valuations.

Source: HolonIQ

And what caused the bust? Investors were spooked by a pretty poor performance from Coursera and Udemy post-IPO, and a shaky first year from Duolingo (it’s since bounced back, though I’m fairly convinced it is not an effective way to learn a language - which will hit its long-term prospects).

Byju's, the A-Lister of the EdTech world, fell off the wagon: firing thousands of employees, pissing off its international lenders, and ultimately shedding a lot of zeros from its sky-high valuation.

The drop in investment is not a death knell for EdTech, but it’s certainly a reality check: and it also places new pressure on companies to find a route to profitability.

2. Lifelong learning will expand

Lifelong learning will become more important. The vast majority of the population are working-age adults, yet they get just a fraction of the spend on education.

There’s a few reasons I think that will change.

The continued move towards a knowledge economy: the knowledge economy is one based on intellectual capacity and ideas. More and more jobs are now focused on what you know (what knowledge you possess), and what you are able to do that others can’t (what skills you possess) - both things that can be obtained through lifelong learning.

Digital transformation: jobs are being created in areas like software engineering, data analysis, digital marketing etc. These are functions that did not exist 50 years ago, or if they did they looked dramatically different. Even compared to ten years ago, the dynamics of working with tech are fundamentally different (Exponential by Azeem Azhar is a great book that shows just how fast tech is accelerating). Adult learning is a necessity to keep up. Many jobs that exist today may not exist in the future - and many jobs that exist in the future cannot yet be imagined today.

Personal and professional growth: according to LinkedIn, 76% of Gen Zers believe learning is the key to a successful career. In the face of a move towards job hopping rather than job-for-life, companies will turn to learning as a key benefit that can be given out to employees relatively cheaply (compared to say, healthcare or long sabbaticals).

Other factors: like the fact we are now living longer lives, so naturally will need to have more ‘injections’ of education to keep up with the expanding body of global knowledge and new technologies.

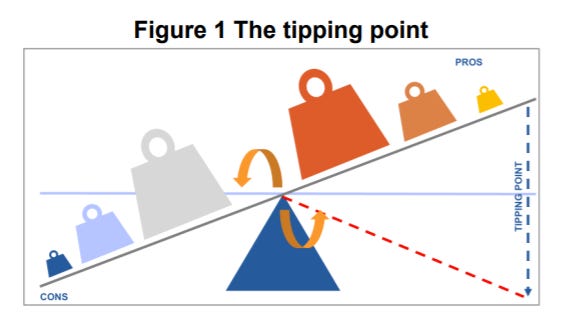

A nice metaphor to sum all this up comes from a 2018 DfE paper into adult and lifelong learning: “the trigger to participate in learning for each adult comes at a tipping point where personal benefits (or ‘pros’) outweigh personal costs (or ‘cons’)”.

The factors listed above are universal factors - the pros for all of us to engage with learning. Individuals will also have their own pros (such as desire to enter a specific career, learning a language for travel, keeping up with the interest or work of a spouse). It makes sense that universal pros coupled with individual pros are tipping the scale for a lot of people.

The scale is also becoming universally lighter on the ‘cons’ end. There are fewer barriers to access lifelong learning.

New markets and new technologies are enabling course content to be more accessible and cheaper.

The government is supporting a greater range of qualifications and investing in lifelong learning options.

Apps and gamification are making learning fun and habit-forming.

New models enable costs to go down (such as MOOCs, online tutoring, advertiser-funded).

More choices are enabling learners to select a course and delivery mode that matches their lifestyle.

Individual factors will still play a role in this tipping point, but if we look at the universal weights on the scale - they are shifting in favour of lifelong learning.

3. India will be the key market

India is going to be the market to watch for EdTech.

There is appetite and progress towards radical educational transformation. The National Education Policy sets out the biggest set of changes to education in 30+ years. Expenditure on education will increase from 3% of GDP to 6% of GDP, India’s HE system will be opened up to international universities (several top UK, US and Australian unis are already eyeing this up), and the school curriculum will be overhauled.

The best explainer of the plans is in this Indian Express article.

The NEP is a long-term, 20-year plan that will reshape education policy in India, and the opportunity for tech solutions here is huge.

Not only that, but the market is enormous: there are 1.5 million schools in the country and 250 million students, and a huge market for test preparation that exists on a scale several times over that in the UK, Europe and US.

A straightforward look at the numbers might suggest that it is China that will become the EdTech superpower, and that India is at risk of stagnation.

But there are a few reasons I’d steer clear of a big bet on China. The main is China’s trigger-happy approach to regulation. The country's 2021 crackdown on EdTech firms risked crushing a bunch of firms. As explained in this TechCrunch piece, China introduced a “ban on any for-profit tutoring services focused on the country’s core public school curriculum, oriented around the make-or-break high school and university entrance exams. Limits were also set on the times during which students could attend classes, restricting class schedules to no later than 9pm on weekdays, and allowing only extracurricular courses on weekends.”

In the same year, China launched a widespread crackdown on tech across the board that is wiped billions from the valuations of tech companies operating in China.

So we have two countries that, over the last five years or so, have fuelled huge international EdTech growth. One of them is opening the doors to globalisation and innovation - while the other has a history of clamping down and imposing restrictions. That’s why I chose India are the main market for EdTech growth in the years ahead.

4. A data-driven learner management system will come along

By and large we’ve come to the conclusion that AIs and self-directed learning models aren’t going to replace teachers. Students of all ages benefit from someone to inspire and motivate them, model and scaffold for them.

The future of EdTech in the classroom, then, is supplementing teachers with technology and insights. It’s this insight piece that I think will really take off in the not-so-distant future. With masses and masses of data and increasing pressure to ensure high attainment for every student, there is a gap in the market for a user-friendly system that is gathering and evaluating data. Identifying links between test scores, attainment, attendance, homework - even other metrics like how much a library card is used.

A piece of technology like this would enable schools to identify (a) the impact of simple, costless interventions on outcomes, and (b) the right time and the right students that those interventions will be most beneficial for.

Where data can be useful is in evaluating what practical interventions do work and for who. In other words, teacher-led learning that is supplemented by adaptive learning tech.

Schools have all of this data, and teachers are often at pain to collect it. There is, at least as far as I can tell, no piece of software that is putting all of this data in one place, making it easy for teachers to input, and using it to evaluate what works, what doesn’t, and when students require interventions.

5. Tutors will replace MOOCs

MOOCs are Massive Open Online Courses - essentially online, distance learning courses that enable an unlimited number of students to study a course at their own pace, any time. They are self-led courses often made up of pre-recorded lectures and content that students move through at their own pace.

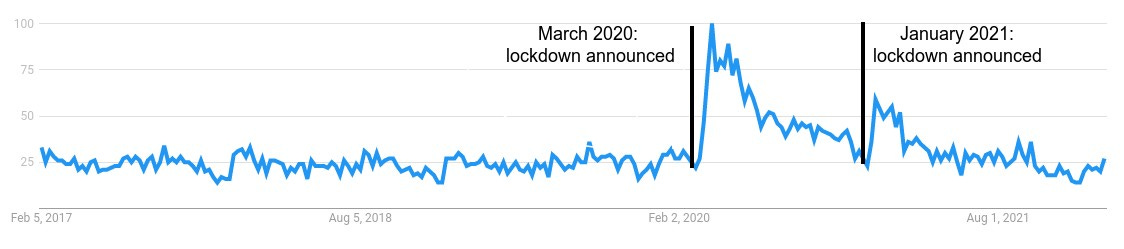

They’ve had a good couple of years. More time at home, coupled with furlough, has meant that online learning platforms saw a surge in 2020. Google Trends, which shows interest in phrases like ‘online courses’ peaked when lockdowns were announced, then waned as restrictions were eased.

We’re already seeing huge growth in tutoring: the UK government invested in tutoring as a solution to help COVID-affected students catch up, GoStudent has become Euorope’s most valuable EdTech, and language learning companies like Preply are focusing their efforts on tutoring rather than self-directed study.

There’s two reasons I think tutoring apps will grow faster than MOOCs in the years ahead:

1. There’s a low barrier to entry for tutors and content creators. If you look at a MOOC, you need large groups of qualified professionals to be creating content - and lots of it. You need to create an entire course worth of content, and you can’t really soft-launch or build as you go, because you need a working platform and enough content to always keep up with the fastest learners. Whereas these tech-enabled tutoring platforms are eliminating any sort of barrier to entry. Anyone with the skills can become a tutor and make money. There’s no set hours, they can do it alongside their jobs - so there’s less of a recruitment challenge. Uber had similarly low barriers to entry for drivers (which brings with it its own issues) - but it was crucial in enabling them to scale rapidly. Tutors are then creating content of their own volition, building curriculums as they go, and sharing resources with other tutors: again facilitating scaling.

To put this point into perspective, if I operate a MOOC and want to launch a course on linguistics, I need to employ a linguistics academic (and possibly several) to develop course content for the entire programme. If I want to award credentials, that course content may have to go through quality-controls from regulators or awarding bodies. I need to ensure there is enough of a market for the course that a community remains active to provide peer-to-peer support. My course cannot go live until all of those steps are completed.

If I’m a tutoring company that wants to start a linguistics course, all I need is one linguistics tutor - who is self-employed, designs their own content, and manages their own cohort.

2. Tutor-directed learning addresses the biggest problem with MOOCs: motivation and drop-off. Just 4% of people who start a MOOC will actually complete it. And, most unbelievably of all, this figure didn’t improve between 2013 and 2017. That suggests that, even with a wealth of data about the interventions that can improve completion rates, there’s something about MOOCs that means people rarely complete them. It seems obvious to me: without a human personalising your learning and holding you accountable, it is too easy to drop-off. There is a very low barrier to signing up to a MOOC, and the barrier to dropping off is just as low.

For MOOCs, most people tend to take on free or low cost courses that offer professional or personal development, rather than expensive MA courses that result in a qualification. This suggests to me that it isn’t the credential people want, it’s the learning experience. And the vast majority of people would choose one-to-one tuition from an expert over one-to-many, pre-recorded content.

One of the things I think is most important when we look at EdTech is how we prioritise the technologies that are bridging the gap between underserved communities and privileged communities. Both MOOCs and tutoring certainly have the potential to bridge that divide. But the problem is: MOOCs don’t. The vast majority of MOOC students come from the wealthiest and most well-educated parts of a population. Whereas tutoring is proven to benefit those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, or without access to personalised and stable learning resources.

(By the way, if you’re interested in this I’d recommend Failure To Disrupt by Justin Reich. It’s the best book on why MOOCs haven’t been as transformative as they set out to be).