5 elections

The world voted

2024 has been a bumper election year. Half the world voted in national elections (and there are still a few elections left to run!), making this year the biggest global election year in history.

There were far more than 5 elections this year - there were 5 in July alone! - but across my newsletters I wrote about 5:

What do those five elections - and the other 60-odd - tell us about the state of the world?

Against the incumbents

In the UK, the Tories took punishment at the polls. In the USA, the Democrats were evicted from the White House. In South Africa and India, the incumbents lost significant vote share (both from positions of extreme strength).

But it’s the same story in much of the world. Macron’s gamble on a snap parliamentary election saw his party drop to third place. Portugal flipped from a left-wing government to a right-wing one; Sri Lanka flipped in the other direction.

In Botswana, a single party has ruled since the country’s independence: this year, that party got booted out at the election.

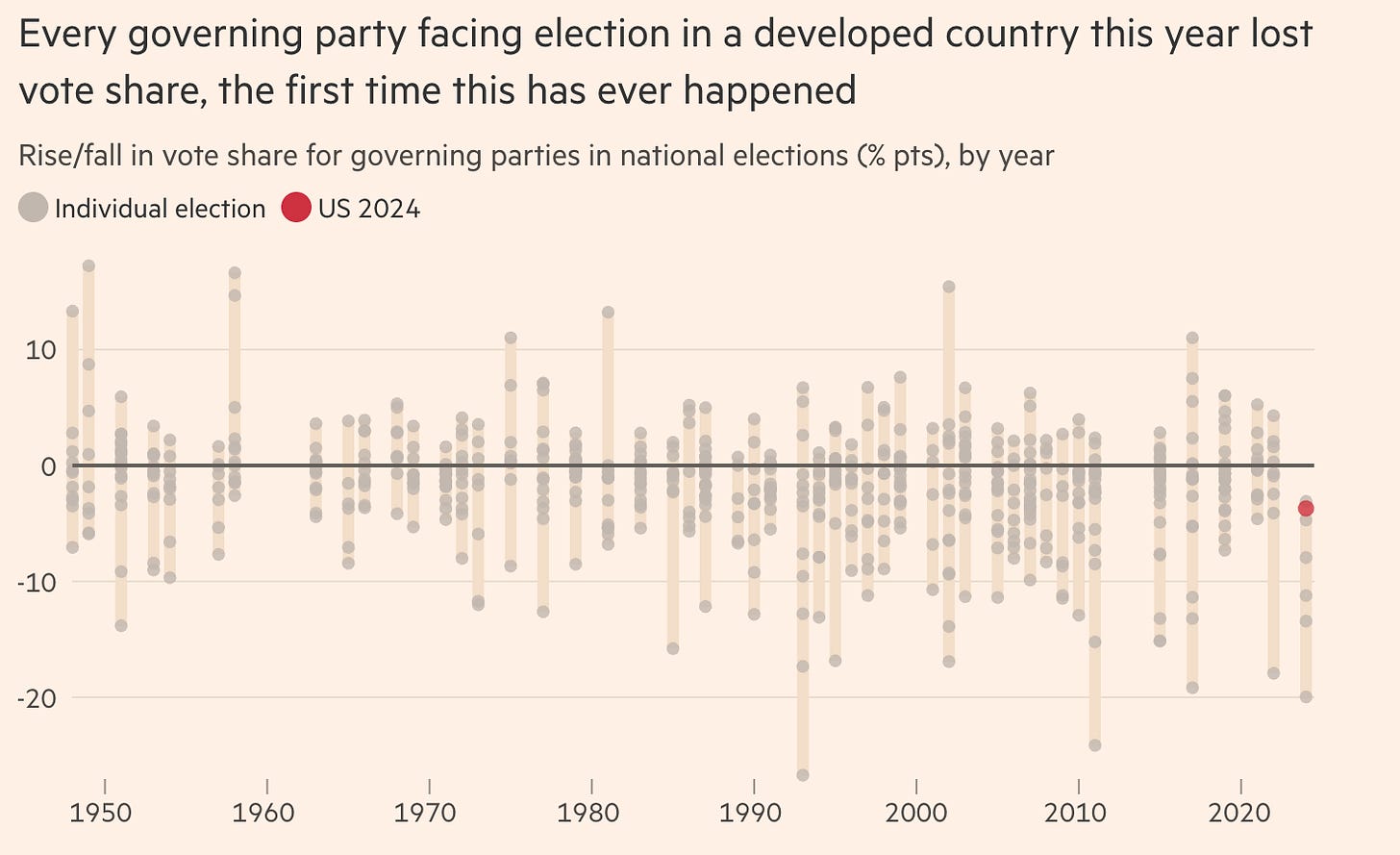

To sum it up: there’s not been a big shift to the left or to the right, there’s just been a big flip from incumbents to newbies. With limited exceptions, voters wanted something new this year.

So why has it been such a bad year for the incumbents? The global nature of the shift suggests it’s not necessarily something the individuals have done, but a case of being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

The world is at war: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has dragged on far longer than expected, and the situation in the Middle East seems to only be worsening.

War itself might be alarming enough for voters to switch sides, but the knock-on effects definitely are. Rampant inflation has been a global effect of the wars, as well as that massive pandemic: and countries are punishing the leaders that oversaw it.

The developed world has also seen a pretty enormous spike in immigration: creating space for anti-immigration parties to come in and steal votes from incumbents.

Don’t mention the weather (or the robots)

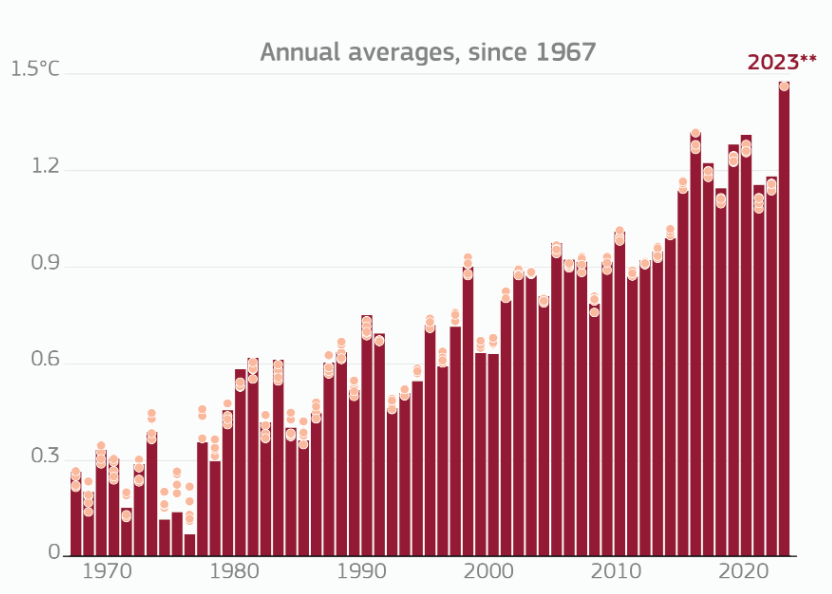

We’re starting to visually see the effects of climate change: the weather is getting wilder and things are heating up. 2023 was the hottest year on record but we look set to break that record this year.

I’ve written before about how unbelievable - and frankly stupid - it is that this has become a political wedge issue. Even excluding the fact it’d prevent our impending doom, transitioning to net-zero would be good for the world (and especially for the countries that get their first).

Election watchers will have noticed policy on climate change was conspicuously absent from the global manifestos and election speeches.

It might not be there today, but soon it will have to be. One of the big reasons for Modi’s losses in the Indian election was widespread discontent from farmers: climate change is a hidden hand making their jobs harder and their yields smaller.

Similarly in the UK, parties may not want to mention the weather when the sun is shining, but voters will expect to see a serious plan on climate change when they’re up to their knees in floodwater.

Another issue missing from the campaign - AI. For all the fears that AI deepfakes would upend this election year, it didn’t really happen. There were a few isolated incidents, including one fake recording of Sadiq Khan, but nothing that seemed to move the needle.

(Incidentally, one commentator was fooled by a pretty obvious AI deepfake of the major UK party leaders playing Minecraft together…)

Though AI did not cause problems in this election, it doesn’t mean it won’t upend the economy in years to come. Just like climate change, it was absent from most global political plans. But politicians across the globe have got to get serious on this (one thing Rishi Sunak was doing well): both mitigating its risks, and grasping its opportunities.

The season finale

Most ballot boxes have now been put away until the next election season rolls around, but there are still a few countries left to vote.

Chief among them, and one that is especially worth watching, is Romania. I suspect it could be a defining election for Europe and the democratic globe.

In the first round of voting, a surprise victor emerged: Calin Georgescu. He’s decisively pro-Russian (in a country that borders war-torn Ukraine) and he doesn’t belong to any political party. The guy barely registered in the opinion polls, yet suddenly on election day walked away with almost a quarter of the vote.

You’d be forgiven for thinking something doesn’t sound quite right - and you’re not the only one. Romanians are now considering a re-run of the election, with a court verdict pending, in large part due to what seems to be foul play from TikTok.

Last week, I wrote about the dangers of TikTok for young kids - but its democratic dangers are also being underplayed. Remember - this is an app that is highly addictive, surprisingly influential, and ultimately under the thumb of an adversarial foreign power.

TikTok, then, could be a new kind of weapon in the 21st century information war: a tool to distort, distract and disseminate at the will of its owners.

If the CCP were using TikTok in this way, it’d be a pretty powerful weapon. You could tear a country’s social cohesion apart from the inside by serving increasingly radical positions on fringe issues to users… it’d explain a lot.

The Romanian investigation seems the closest we’ll come to finding out whether TikTok is being used as a tool of mass-manipulation. If they rule that it is, there will be a lot to answer for: and we’ll find ourselves staring down the barrel of an enormous upheaval to democracy as we know it.

Romania is bringing a real season finale to this democratic year.

Great links to previous posts