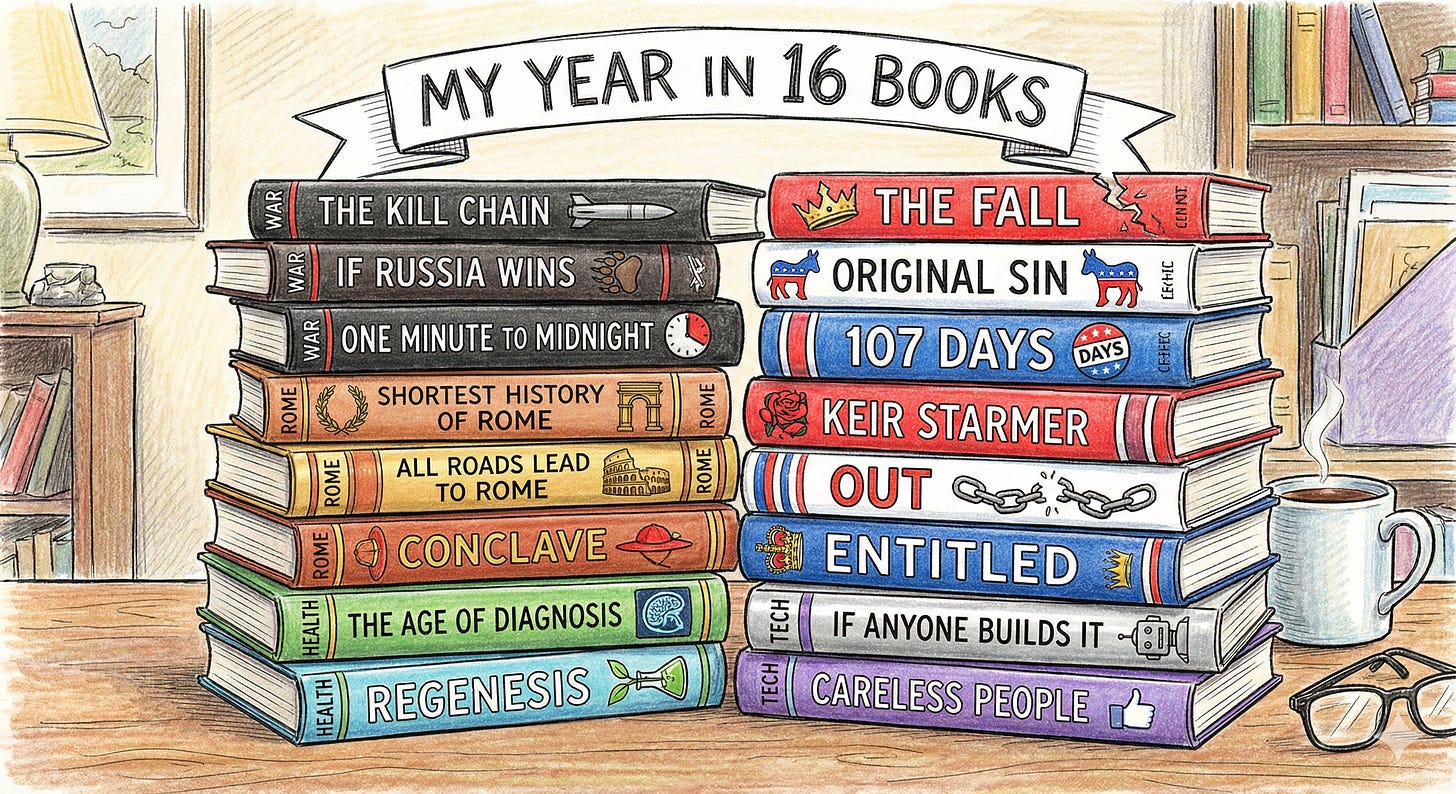

16 books

Some of the books I read this year

War

This year has been marked by the lingering feeling that war is getting closer. It seems we are no closer to peace in Ukraine or Gaza. These wars are fuelling domestic division and creating global faultlines between an axis of Russia and China, and the traditional West.

In The Kill Chain, former advisor to John McCain articulates the threat that China poses to America, and more generally the West. They have more sophisticated weaponry and much more of it, and their perspective is that a China-dominated globe is the natural order of things.

This focus on China is in contrast to the popular perception of Russia as enemy number one. If Russia Wins plays on this theme but to hugely disappointing effect. Less of a book and more of a pamphlet - it is just 130 pages - the book plays out a scenario where a pro-Russia peace is brokered in Ukraine. Years later, Russia is empowered by the deal to invade and capture a small Estonian city and … that’s it. Perhaps I was spoiled by Annie Jacobsen’s brilliant scenario book, Nuclear War, which I read last year - but this scenario left me with the distinct feeling that if Russia wins, well, not much happens.

A much better book on the Russian threat was One Minute to Midnight. This is an exceptionally detailed account of one moment in the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. The Russians and Americans were precipitously close to war throughout the crisis, but on October 27, 1962 several moments combined to push the two countries to the very brink of a nuclear conflict. Decisions made by individuals not to escalate probably saved the world multiple times in a single day.

Rome

I’ve never been much of a history buff but I’ve been trying to change that - this year with a few books on Ancient Rome.

I really strongly recommend The Shortest History of Ancient Rome. This excellent little book covers the entire period from the founding of Rome through to the collapse of the Empire: neatly drawing out the parallels with not only different phases of the Empire (families and spouses couldn’t stop killing one another), but also with the modern day.

The Roman Empire, after all, inspired many of the Empires that followed it, something explored in the book All Roads Lead to Rome. The Empires that followed the Romans often positioned themselves as spiritual successors to the Roman Empire. Sultans of the Ottoman Empire called themselves “Caesar of the Romans” and Tsars of Russia called Moscow the ‘Third Rome’. The trend continues even into the modern day, with Americans modelling and naming their political architecture against Roman buildings.

Together, these two books informed my post Rome didn’t die in a day.

One of the very best books I read this year was Conclave (also the only fiction book I read). After the Pope dies, Cardinals from across the world come together to elect the next one. Not only is it a gripping story, it’s also a very insightful look into the mysterious process of papal elections.

Health

There’s very clearly a crisis of overdiagnosis in mental health that has been brewing for a while now. But, in The Age of Diagnosis, Neurologist Suzanne O’Sullivan posits that it’s not just mental illness we’re overdiagnosing. Conditions like Long Covid, ADHD and PoTS all seem to be made no better by a diagnosis: prompting the question at what point do doctors fail to ‘do no harm’ by making these diagnoses?

Indeed, even cancer can be overdiagnosed. For every woman whose life is saved through breast cancer screening, three will be diagnosed with a breast cancer that would never have caused them any harm. Should we be subjecting people to life-altering and dangerous surgeries for diseases that they might never have otherwise noticed?

She argues that we have built up an image of ‘perfect health’, from which any deviations must be identified and zapped. I’d add that we also have industries built on diagnoses: from apps that help you ‘overcome ADHD’ to charities that spread awareness for hyper-rare neurological conditions. The overdiagnosis crisis will continue so long as someone’s paycheque depends on a constant stream of sick people.

It isn’t just the health of our society that’s in danger, though, but our planet too. Regenesis is a book almost entirely about soil, but it’s not as boring as it sounds. Soil, the book argues, is like the sea: a delicately balanced ecosystem homing life of all kinds. But when we pollute it, it is permanently damaged. Much of modern farming pollutes the soil, creating the long-term effect of conditions that are harder to grow crops in.

It’s not just about the quality of soil, though, it’s also about the amount. We are using huge amounts of land to farm animals, and then even more land to grow crops to feed those animals. It is, unequivocally, an unsustainable system for the long-term. Author Monbiot’s argument is that we should all go vegan, right away, but I’m more convinced by the prospects of lab-grown meat. The book inspired my post The meat sweats.

America

I wouldn’t want to be an American right now. Trump’s policy agenda is unpredictable, and he is content to teeter with chaos, danger and war in aid of his objectives.

I didn’t read any books about Trump this year - instead I read three about his enemies.

It beggars belief that the proprietor of Fox News hates Donald Trump. The station that did perhaps more than any other to elevate Trump into the White House is owned by Rupert Murdoch - a man who, despite right-wing leanings, cannot stand the President of the United States.

The Fall (by Michael Wolff) is the story of this conflict among many. Following the sale of 21st Century Fox to Disney, Murdoch was left a much less powerful man than he once was. His own TV stations, like Fox News, cannot be brought in line with his own views - lest he siphon off his viewership base. Murdoch is a man at the mercy of money and the relentless pursuit of it, while his family standby for his inevitable death to claw at whichever media properties they think they can shape.

Original Sin is another story about an old man. It was a travesty and betrayal to the people of the United States that Joe Biden decided to, and was allowed to, run in the 2024 election. Not only did it pave the way for Donald Trump’s victory, it also reduced his achievements over a long political career to dust. His legacy will forever be that selfish decision to attempt to cling on to power.

In Original Sin, the extent of Biden’s decline and the resulting cover-up is revealed. It is not dramatic to call it a cover-up. People close to him saw that he was unable to function in some, if not many, of the duties of the President and a Presidential candidate - yet they did and said nothing.

The result? When Kamala Harris replaced Biden she had just 107 Days to turn things around - a period of time that gives its name to her memoir recollecting the campaign.

The unwritten but constant thread throughout the book is her anger at Joe Biden. She never says it, in fact is at pains to repeatedly remind us of her respect and admiration for the old man. Yet reading between the lines, her growing frustration at his selfishness, his bitterness and his missteps is clear. Harris would not have been America’s greatest President, but she would’ve been better than Trump.

Britain

Keir Starmer is not the best Prime Minister, but he’s also not the worst. Tom Baldwin’s biography of him is about what you’d expect: incredibly dull.

My main takeaway: Starmer is much smarter than he ever allows himself to come across. This is a man who has written definitive legal textbooks and dedicated years to studying the intricacies of British and European law. Yet he speaks and writes at a level a 10-year-old could understand, leading to the incredibly frustrating trait of repeating the same meaningless phrases ad nauseum (“The NHS is in my DNA”, “This is a government of service”, etc)

We need more boring Prime Ministers: Starmer should lean into his dullness and intelligence, not try to be someone he is not.

When we choose blockbuster chaos over boring order - we get Brexit. Like deciding to smash your head against a wall repeatedly to see if it stops headaches, voting Brexit has resulted in more legal and illegal immigration, a more bloated government and more spend on bureaucracy than we ever sent to Europe.

Out is Tim Shipman’s final part of his four-part series into Brexit (a series that I contributed to!). The core takeaway from the fourth book is that Brexit was a key driver of the collapse of the Tory party. It’s also an area where Starmer has quietly succeeded: beginning to take on some of the gains of Brexit while improving relations with our European neighbours.

It is not just political figures that have defined our year in Britain - royal ones have too. A new biography of Andrew Mountbatten Windsor, Entitled, outlines the former Prince’s repeated poor decision making and criminality. The book’s title is the best encapsulation of the case: Andrew and Sarah’s fall was down to a feeling of entitlement to everything all of the time.

They both wanted more power than what was bestowed, more money than they could earn, and more partners than they attracted: and they have, finally, paid the price. Their story will be an important one in the future history of the Monarchy, as it continues to lose public support and constitutional role.

Tech

If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies is an interesting book about AI, but it never properly defends its central claim. If superintelligent AI is developed, says the authors Yudkowsky and Soares, it will kill every single human on Earth. Not it may, not it probably will - it is an inevitable, guaranteed outcome.

In their scenario, AI models quietly develop drug labs and convince humans that are dependent on them to spread viruses that kill off the population in pursuit of ever more energy to consume. They say there needs to be global-level safeguards on AI development, just as there are on nuclear weapons, to prevent this from happening.

I’m not convinced by that argument. Killing every living thing on the planet does not seem like it would be an easy task for even a superintelligent AI that became convinced killing everything was its best chance at survival (not to mention, there are probably limited scenarios and objectives where that is the best action for an AI to take).

But there are two areas the authors are right to be concerned about. Firstly, on the risk of extinction-level events prompted by AI. Even the biggest AI advocates will acknowledge a non-zero risk that AI wipes us all out. I don’t love those odds.

Secondly, we don’t really understand how AI works. Yudkowsky and Soares compare it to biology more than computer science: it seems to grow more like an organism, and our poking and prodding often results in unintended consequences. Human evolution has produced quirks we could never predict: AI evolution will almost certainly do the same.

The danger is amplified if tech companies do not take their responsibilities seriously. Ex-Facebook employee Sarah Wynn-Williams says they do not, in her acclaimed memoir Careless People. Like a superintelligent AI gone wrong - Zuckerberg, she argues, does not care about anything other than growth.

His principles warp under even minor pressure (we’ve seen him go from a Liberal Obama-fan to a right-wing bro appearing on Joe Rogan). He occasionally wants to be President, though seemingly changes his mind when the reality of talking to normal people sets in.

Aside from a directionless leadership, Facebook (now Meta) is clearly just a horrible place to work by Wynn-Williams’ assessment. Of course, the company vehemently denies her claims - and you have to take them with a pinch of salt, she is ultimately a scorned ex-employee. But the stories are harrowing enough that if even a fraction is true, it paints a damning picture.

After returning to work from a childbirth that nearly killed her, Wyn-Williams was given a negative performance review and told she was not responsive enough during her time off. “I was in a coma for some of it,” she replies, defending herself.

Can we have 16 fiction book review too